Como buenos amantes de este mundillo del vídeo, imagino que hoy habréis visto que se ha anunciado una nueva versión de la PXW-FS7, la FS7 II (oficialmente, la referencia es PXW-FS7M2). De hecho, tengo un par de vídeos (los típicos aburridetes que subo yo, en castellano y en inglés, en mi canal de YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCMUk_ztypSGRWw23mawsi0g/videos ).

La PXW-FS7 se anunció -¡cómo pasa el tiempo!- hace ya dos años en el IBC. Recuerdo, que, meses antes, me había llamado la atención su diseño. Veníamos por aquel entonces de cámaras muy potentes, con sensores ya en tamaño Super35, pero con “configuración de cajita”: estaban pensadas para envolverlas en accesorios prácticamente desde el principio. Sí, me refiero a la PMW-F3 y, especialmente a las NEX-FS100 y FS700. Otras marcas, con mayor o menor suerte, iban por derroteros parecidos. Pero, de repente, algo nuevo aparecía. Ya estaba totalmente interiorizada la fiebre por el sensor grande. Ya sabíamos que podíamos reciclar nuestras “viejas” lentes mediante adaptadores y seguir sacándoles todo el jugo. Pero cuando me puse la FS7 en el hombro en septiembre de 2014, entendí que ese diseño tan curioso tenía una finalidad muy clara: poder trabajar con una cámara “con estética de ficción” de manera muy similar a una ENG de hombro… e incluso mejor.

Un año después se presentó la FS5. Mucha gente la consideraba la hermana pequeña, aunque, dependiendo de en qué nos fijásemos podría ser incluso superior. Lo más significativo fue el filtro de densidad neutra variable electrónico, visto por primera vez en camcorders de Sony en la PXW-X180/X160. Pero ahora iba más allá: podía cubrir totalmente un Super35.

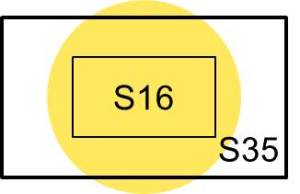

Comparación de tamaño entre una PXW-FS5K y una PXW-FS7K (no la FS7 II)

Y ahora, en 2016, tras recopilar –os lo aseguro- muuuuuuuchas opiniones de usuarios de todo tipo, la FS7 se ha renovado y se presenta la FS7 II.

Un auténtico orgullo haber presentado la FS7 II por primera vez en Barcelona

FILTRO ELECTRÓNICO VARIABLE DE DENSIDAD NEUTRA

Como decía, el FEVDN (bueno, si no os importa, lo voy a llamar “el filtro ND”) significó un cambio drástico al incorporarlo en un sensor con formato “cine”: al pasar de un entorno a cubierto (vamos, un interior) a la intemperie, normalmente tenemos más luz. Los novatos como yo solemos hacer una de estas dos cosas: o cerramos iris (aumentando la profundidad de campo; una pena con un Super35), o cambiamos la obturación (variando la cadencia de la señal). Vamos, en ambos casos, cambiamos la estética de la grabación.

Pero el filtro ND nos cambia significativamente la situación.

Hay tres formas básicas de utilizarlo:

- Con las posiciones 1/2/3 de la torreta de filtros. En la FS7 esas posiciones llevaban los valores ¼, 1/16 y 1/64 serigrafiados. En la FS7 II no; podemos asignar el valor que queramos entre varias opciones, y así dejar, por ejemplo, 1/8 en la posición 1, 1/32 en la 2, y 1/64 en la 3. Viene muy bien cuando hemos podido comprobar previamente a qué posición queremos cambiar de manera muy rápida.

- Con un ajuste “analógico” (que no es analógico, pero da esa sensación): si el filtro está en alguna de las posiciones 1, 2 ó 3, podemos pasarlo a modo “variable” con un pequeño conmutador en el lado izquierdo de la cámara, y así podremos controlar mediante el dial que está justo al lado, o mediante el que tenemos en la empuñadura (se puede ajustar para hacerlo así), para ajustar el valor entre ¼ y 1/128 en incrementos lineales. Esto viene genial cuando queremos “jugar con la luz” que llega al sensor… ahí lo dejo, que hay muchas maneras creativas de sacarle partido.

- Con un ajuste automático. A mí me gusta asignar esa opción al botón “2”, también en el lado izquierdo. Así, la cámara controlará el filtro ND automáticamente para mantener, en la medida de lo posible (vamos, dentro de ese rango ¼ – 1/128), la luz que llega al sensor constante. Es decir, tú preocúpate del foco, no del iris o del shutter.

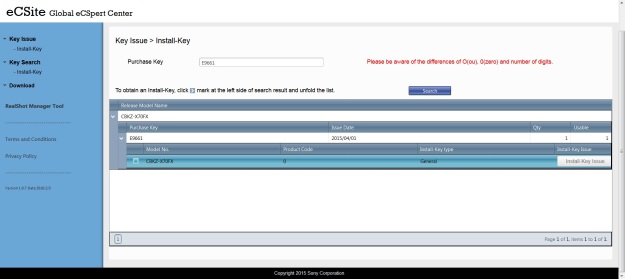

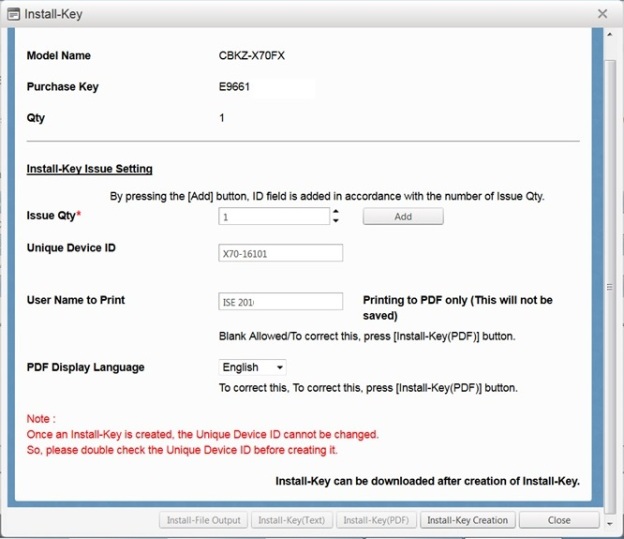

Vale, pero, ¿cómo funciona?

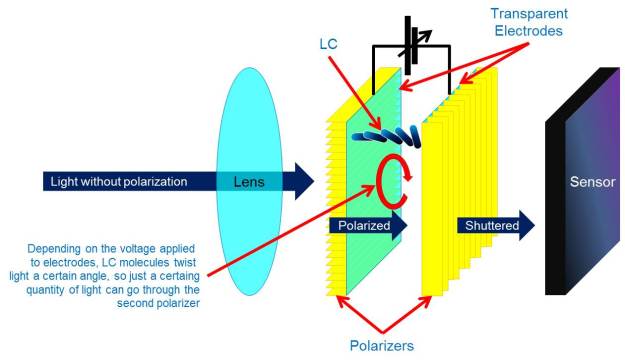

Casi todos sabéis cómo funciona un filtro ND externo: dos polarizadores lineales que, dependiendo del ángulo de giro entre sí, permiten pasar mayor o menor cantidad de luz. Pues bien, el filtro electrónico variable de densidad neutra es básicamente lo mismo, pero a nivel microscópico, y en lugar de rotar los filtros, se rota la luz entre ellos mediante una capa de cristal líquido.

La luz viene de la lente sin polarización; se encuentra un filtro que la deja “peinada”. Luego atraviesa un electrodo transparente, la capa de cristal líquido, otro electrodo, y finalmente otro filtro de densidad neutra, que puede estar girado 90 grados respecto al primero (ojo, no sé exactamente si se mantiene con 90 grados o vuelta entera; es una explicación teórica). Dependiendo de la cantidad de voltaje que se aplique sobre los electrodos que rodean el cristal líquido, sus moléculas girarán más o menos, como si fuesen una hélice, girando en mayor o menor medida la luz que pasa a su través.

MONTURA E TIPO “LEVER LOCK”

La verdad es que no sé cómo traducirlo… ¿con bloqueo de rosca? Bueno, lo dejo en inglés.

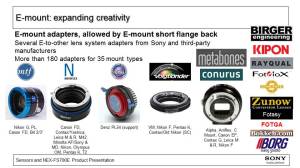

Como sabéis, uno de los puntos fuertes de la montura E es que permite usar prácticamente cualquier lente del mercado, puesto que la distancia sensor-montura (“flange back”) es muy escasa, de tan solo 18 mm. Así, cada uno se “construye” su propia lente mediante un adaptador.

Pero en un entorno profesional como el broadcast o el cine, es muy habitual que esas lentes o bien sean pesadas y grandes, o bien estén “atrapadas” por varios accesorios, como barras, mattebox, follow-focus… y resulta difícil en algunos casos girar la lente para poderla anclar a la montura E.

Así que la solución ha sido adoptar una configuración parecida a la que tenemos en la montura PL: se inserta la lente frontalmente sin girarla, y se bloquea mediante un pasador circular.

Confieso que las primeras veces me ha costado un poco acostumbrarme a montar y desmontar las lentes así, puesto que esta montura lleva un pequeño bloqueo para evitar que se deslice el anillo de fijación, y hay que pensar bien hacia qué lado hay que desplazar ese “collar” antes de pulsar el desbloqueo. Pero una vez usada, la verdad es que me gusta. Y mucho. Ah, y además tiene, obviamente, la interfaz para control de la lente e intercambio de datos con ella, y, como es lógico, todas las lentes con montura E se pueden montar.

MEJORAS MECÁNICAS

Prefiero englobar todas estas novedades “ergonómicas” de la FS7 II en un solo punto, para no fragmentar mucho este artículo.

En primer lugar, si recordáis cómo era el brazo de la FS7, llevaba por dentro dos tornillos que había que aflojar para extender o contraer la distancia entre la empuñadura y el cuerpo de cámara. Obviamente, era necesario un destornillador plano o una moneda, y no era muy práctico en caso de querer trastear rápidamente. Ahora, en la FS7 II, en lugar de tornillos tenemos palomillas en el lado exterior; de hecho, únicamente una de ellas fija la parte interior del brazo, lo que significa que, sin herramientas, podemos prolongar o contraer el brazo tocando una sola palomilla.

La otra palomilla que veis es la que se inserta en la roseta Arri del lateral. Pero, si deslizamos un poquito el brazo, vemos que hay un agujero; si ponemos ahí esa palomilla, podemos poner el brazo paralelo al cuerpo de cámara, la empuñadura en la parte frontal derecha, y así trabajar de una manera muy similar a la FS5 para hacer contrapicados, con la cámara apoyada en nuestra barrigota.

Ah, y aunque suene gracioso poniendo el brazo hacia atrás, ¡podemos dejar la cámara en una mesa conservando su decencia, sin acostarla! 🙂

Ahora en el lado izquierdo, un detalle que ha cambiado bastante es el brazo que soporta la pantalla LCD. Muchos habéis comentado que, con el tiempo, y dependiendo de la humedad, de algún golpe, de la holgura que tenga… la pantalla LCD se suele “caer” en la FS7. Para evitarlo, en la FS7 II dicho vástago ya no es cilíndrico, sino de corte cuadrado. Así, no hay manera (civilizada) de que la pantalla se nos gire hacia abajo. Esa barra apoya sobre unos adaptadores que, a su vez, están encajados en las bisagras; si preferís usar barras de 15 mm, simplemente hay que retirar esos adaptadores.

Nos quedamos en la pantalla, y ahí hay otro pequeño detalle que nos hará la vida más cómoda. Si habéis intentado enganchar la “lupa” (el “eyepiece”, pero… ¿valdría monocular?) al LCD de la FS7, posiblemente os hayáis sentido un pelín torpes. A todos nos pasa; el hecho de tener que apretar casi a la vez la grapa superior y la inferior al final nos hace posar la cámara en una mesa o el suelo, y enganchar cada grapa con una mano. Pues en la FS7 II, la parte superior es un vástago fijo, que engancharemos primero, y es únicamente en la parte inferior donde tenemos que fijar el clip. Y lo podemos hacer con una sola mano, en un gesto más natural.

Aparte de ese monocular, ahora en la FS7 II se incluye una visera plegable que ocupa muy poco espacio al estar plegada, pero que nos ayuda mucho cuando estamos grabando en exteriores, para evitar reflejos. Insisto: se incluye de serie. Y la forma de asirla a la pantalla LCD es igual que el monocular, aunque la pestañita inferior que se usa para tirar del clip para fijarlo es más corta que la del monocular.

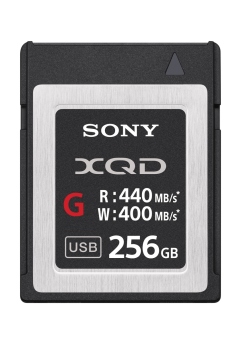

Otra parte que ha mejorado es la forma de extraer las tarjetas XQD. Si veis a algún videógrafo con las uñas extrañamente largas y puntiagudas, puede ser un guitarrista o un usuario medio de la FS7, puesto que el espacio que nos queda para sacar las tarjetas requiere de precisión milimétrica. Ahora en la FS7 II sobresalen 8 mm, lo que permite sacarlas sin necesidad de succionar. 🙂

Alguna FS7 nos ha llegado alguna vez con la tapa de la parte de audio rota: se la dejaron medio abierta, golpe, y ¡cras! La tapita de la FS7 II no se despliega en horizontal, sino que “cae” verticalmente, para evitar accidentes.

Por último punto de este apartado, hay una situación que más de una vez nos ha ocurrido: quieres empezar a grabar, pero no hay señal en la pantalla. Revisas que la cámara encendida…ok. Batería suficiente… ok. ¿Es posible que me haya cargado la cámara justo hoy, que tengo el rodaje más importante de mi vida? Desconectas el visor lo vuelves a enchufar, y voilá; eso era. No lo habías conectado bien. Pero a ver quién te quita el susto ahora. Pues bien, en la FS7 II, y aunque no sea la innovación más innovadoramente innovadora del mundo, hay un LED verde (no es muy intenso; no creo que genere reflejos incluso a oscuras) sobre el deslizador de encendido y apagado. Vaya historia os he contado para decirlos que tiene un dichoso LED de On/Off, ¿eh?

BOTONES ASIGNABLES

Llamadme raro (¡raro!), pero, personalmente, no soy muy amigo de usar pantallas táctiles en lo que uso como monitor. En el móvil lo sobrellevo con terapia, pero en una cámara me da mucha rabia ver grasaza o protector solar sobre la pantalla.

Vamos, que prefiero los botones. Y botones a los que no tenga que mirar para localizarlos ni presionarlos.

Pues eso es lo que hay en las FS7: botones asignables con forma de “donut” y con una ligera rugosidad en el “anillo” para poderlos localizar fácilmente. Pero es que en la FS7 II tenemos la friolera de ¡7 botones en el cuerpo de cámara! Si les sumamos los tres que tenemos en la empuñadura, nos ponemos en 10.

Como cabría esperar, a cada uno de esos 10 botones les podemos asignar las mismas funciones de que ya disponíamos en la FS7, más las relacionadas con el filtro ND. Como os decía antes, personalmente me gusta poner el botón de ND automático en el botón 2.

Asimismo, me gusta utilizar el «dial» de la empuñadura para ajustar el filtro ND, si es que no lo estoy utilizando en automático. La empuñadura sigue teniendo los mismos botones asignables (4, 5 y 6):

SENSOR

El sensor es exactamente el mismo que ya utilizábamos en la F5, FS7 ó FS5: un CMOS de tamaño Super35 mm, con resolución 4K y tecnología CMOS. No ha cambiado el espacio de color que es capaz de captar, pero sí se ha añadido un nuevo espacio de color sobre el que puede grabar, el BT.2020, que se añade al S-Gamut3 y al S-Gamut3.Cine de que ya disponíamos.

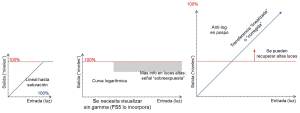

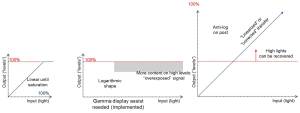

Este sensor, como ya sabéis, nos ofrece un margen dinámico muy grande (sí, HDR), que podemos aprovechar mediante las curvas S-Log2 y S-Log3. Una curva S-Log lo que hace, básicamente, es maximizar el margen dinámico de entrada al sensor (la luz que es capaz de captar) y sacarlo sobre un rango de salida limitado (voltaje o ceros y unos), principalmente comprimiendo las altas luces. La imagen parece muy “lavada”, pero en pospo podemos aplicar una curva “anti-Slog” para linealizar. Pero en las FS7 y FS7 II podemos aplicar unas LUT generadas externamente (por ejemplo, con el RAW Viewer) para poder monitorizar desde cámara con la misma estética que tendrá nuestra imagen final.

¿Que para qué sirve tener un margen dinámico tan grande? Por ejemplo, pensad en una escena en la que tenemos una habitación relativamente oscura con una ventana. Con un margen dinámico “tradicional” (alrededor de 6 stops), tenemos que elegir si exponer bien el interior y sobreexponer el exterior, o exponer correctamente la escena exterior y que se nos peguen la bajas luces en interior. Con una curva logarítmica podemos recuperar ambas zonas, y “narrar” ambas historias.

Además, la FS7 y la FS7 II ofrecen un par de funciones llamadas HiKey y LoKey, que nos permiten, en caso de no disponer de un monitor HDR, usar los 6 stops en la parte de altas o de bajas luces, respectivamente.

Eso sí, un pequeño consejo personal: mucho ojo con la Slog2/3, porque nos solemos acostumbrar alegremente a ellas, y acabamos usándolas en interiores. En ese caso, no es que la cámara sea ruidosa; es que la curva Slog tiene definido un ISO mínimo de 3200. Es decir, las bajas luces nos las estará levantando… y también parte de ruido. Muy orgánico, y muy “bonico”, pero ruido al fin y al cabo. Así que no la uséis para todo; usadla para lo que la necesitéis. Insisto: es mi humilde consejo.

CÁMARA LENTA

Las opciones de cámara lenta se mantienen igual que en la FS7: Full HD hasta 180 fps de grabación interna en NTSC, y hasta 240 saliendo en RAW.

De hecho, uno de los parámetros que nos indica lo bien que se comporta un sensor en lo referente a rolling shutter es la capacidad de hacer cámara lenta: si el tiempo de salida de la información del sensor es muy corto, también lo será, lógicamente, el tiempo que transcurre entre el comienzo de la primera línea y el final de la última. Así, las líneas verticales disponen de menor tiempo para desplazarse por el frame y “diagonalizarse”. Y, por otra parte, como el tiempo de extracción de información del sensor es muy corto, nos permite acercar el siguiente frame mucho más; “intercalar” más ciclos de lectura en el mismo período de tiempo.

GRABACIÓN

Internamente, la FS7/FS7 II es una cámara capaz de grabar hasta 422 con profundidad de 10 bits en resolución 4K con un códec XAVC-Intra. Como podéis imaginar, la cantidad de información a grabar por segundo es bastante elevada; en concreto, de 500 Mbps a 50p y de 600 Mbps a 60p.

También disponemos de códec XAVC en Full HD, y si estamos trabajando en un entorno broadcast, es muy habitual que se prefiera optar por el MPEG-2 422 a 50 Mbps (“XDCAM”), que, aunque menos eficiente, se lo tragan prácticamente todos los sistemas de edición.

Si, además, disponemos del adaptador XDCA-FS7, entre otras funciones disponemos de la posibilidad de retornar señal hacia la cámara para poder grabar en ProRes sobre las mismas tarjetas XQD.

Y si preferimos sacar la señal en máxima calidad, podemos extraer la señal de la XDCA-FS7 en RAW, y grabarlo en: AXS-R5 (a través del HXR-IFR5), Convergent Design Odyssey7Q+ o dispositivos de Atomos. Ojo, porque en este caso, al igual que en la PXW-FS5 + CBKZ-FS5RIF, o el de la NEX-FS700R/RH, la señal no sale en RAW en banda base (un cable 3G-SDI no podría albergar esa señal en 4K), sino que se convierte a datos, y el cable SDI se utiliza únicamente como medio de transmisión, no como cable de vídeo. Por eso, en el otro extremo, necesitamos un equipo que decodifique la señal, y de ahí haga con ella lo que le ordenemos (grabarla en RAW, trascodificarla, mostrarla en el monitor del grabador…).

FS7 (no FS7 II) con XDCA-FS7 y sistema de grabación de Sony: HXR-IFR5, AXS-R5 y batería de olivina. Para la FS7 II es un sistema similar

CONECTIVIDAD

De nuevo, seguimos teniendo básicamente la misma configuración que en la FS7: dos salidas SDI, salida RAW con la XDCA-FS7 (también genlock, referencia, código de tiempos de entrada o salida, soporte para baterías en V, y entrada y salida de alimentación en continua), 2 entradas XLR de audio, y montura MI.

Esta montura MI (“Multi Interface” shoe) permite conectar, por ejemplo, un receptor de la serie UWP-D. Pero desde septiembre disponemos de receptores duales; es decir, a un único receptor montado en el adaptador SMAD-P3D, podemos conectarle dos transmisores; esto viene genial para entrevistas y eventos, por ejemplo. También tenemos, lógicamente, un micro interno en la propia cámara.

Y recordad que la FS7 II, igual que la FS7, puede grabar 4 canales de audio.

En lo referente a conectividad WiFi, se suministra de serie el adaptador IFU-WLM3, que permite que controlemos desde el móvil la cámara a través de la aplicación Content Browser Mobile. Lo curioso es que no es necesario que metamos el SSID y la contraseña que nos proporciona la cámara, sino que, con la tecnología NFC, simplemente se “saludan” y se nos lanza la aplicación en el móvil/tablet (o nos lleva al sitio de descarga correspondiente).

También existe la posibilidad de conectarle un accesorio llamado CBK-WA100 que puede grabar proxies en una tarjeta SD, y transmitirlos incluso a través de un adaptador 3G/4G.

GRABACIÓN EN CACHÉ

Si estamos utilizando la FS7 ó FS7 II para noticias, no es raro encontrarnos en la puerta de salida de algún edificio esperando al famoso de turno. O a que un animalejo salga de su madriguera si estamos grabando un documental. Para estos casos, viene especialmente bien la posibilidad de grabar “el pasado”, lo que ya ha ocurrido. Para eso, por ejemplo en códec MPEG-2 existe la posibilidad de configurar la cámara con hasta 15 segundos de “pregrabación” que se pasarán a la tarjeta en el momento en el que pulsemos el botón de grabación, y a los que les seguirán los instantes posteriores a esa pulsación.

GRABACIÓN SIMULTÁNEA

Recordemos que la FS7 y la FS7 II tienen 3 botones de grabación: uno –plateado- en el cuerpo de cámara, otro en el asa, y otro en la empuñadura. Y, por otro lado, tenemos dos ranuras para tarjetas. Parece obvio que tener la posibilidad de operar sobre una de las tarjetas con un botón y sobre la otra con otro botón distinto es una ventaja tremenda; por ejemplo, imaginad un concierto o un partido de fútbol en los que tenemos todo el evento en trozos “grandes” en la tarjeta B, pero cada canción o cada “highlight” en la tarjeta A. Viene genial no sólo para recuperar algo que se nos puede escapar en la tarjeta A, sino también para sincronizar en edición en caso de estar grabando en multicámara.

Aparte, como es lógico, podemos configurar la cámara para que grabe lo mismo en ambas tarjetas (para tener un backup, o para empezar edición y corrección de color simultáneamente), y también una grabación continua en la que, si una de las tarjetas se queda sin espacio, se empieza a grabar en la otra tarjeta sin perder ni un frame; posteriormente se ensambla el clip al ingestar.

LENTE SELP18110G

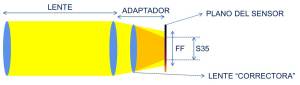

Si habéis trabajado con la lente que venía en la PXW-FS7K, la SELP28135G, sabréis que en realidad en la FS7 se produce un efecto “tele”: perdemos una parte de la imagen que rodea al sensor, y nos quedamos con la parte central, puesto que esa lente está diseñada para encontrarse un sensor Full Frame como, por ejemplo, el de una Alpha A7S II.

Sin embargo, la SELP18110G está diseñada para sensores Super35 y APS-C (en Sony su anchura es igual), así que no tendremos que aplicar ningún factor de conversión.

Se trata de una lente que se activa mecánicamente, así que no tendremos ningún pequeño retardo al operarla. Igual que la 28135, el anillo de foco se puede desplazar hacia adelante y hacia atrás para cambiarlo de manual a automático, pero en este caso lleva ranuras para poder aplicar una rueda dentada de follow focus sin necesidad de adaptador de correa.

La SELP18110G es una F4 en todo su rango de zoom. Puede parecer una lente un poco lenta en angulares, pero está pensada para que al hacer zoom se conserve una profundidad de campo proporcional, sin necesidad, por ejemplo, de retocar iris al abrir plano (y recibir más luz).

OTRAS LENTES

Como ya creo haber comentado, la montura E de tipo “lock lever” simplemente cambia el modo de anclar la lente al frontal de la cámara, pero la distancia entre sensor y borde de la montura, así como las dimensiones del propio anillo, se mantiene. Es decir, podemos seguir utilizando las lentes con montura E (unas 74 actualmente), y, lo que puede resultar aún más interesante, prácticamente CUALQUIER OTRA LENTE DEL MERCADO, sea nueva, antigua, e incluso de menor diámetro que el propio sensor.

Así que tanto si venís de usar lentes EF de fotografía, como si tenéis sus precursoras, las FD, como si tenéis acceso a una buena colección de lentes PL, podéis usarlas sin problema en la FS7 II. Simplemente, tened en cuenta lo que he comentado de si están diseñadas para sensor FF, porque en ese caso quizá nos interese utilizar un adaptador con lente incorporada, para “cerrar” más el cono de luz y cubrir perfectamente el sensor Super35 (y, de paso, ganar 1-1,5 stops más). No entraré en si merece la pena tener una lente adicional en el adaptador para evitar perder angulares y ganar un stop; simplemente, quería mencionároslo (sí, hablaba del famoso Metabones Speedboster).

¿Y qué pasa si la lente es más “pequeña” que el propio sensor? Pues también tiene solución: en lugar de leer toda la superficie en tamaño Super35 y resolución 4K, podemos escanear sólo la parte central con resolución Full HD. Así, esas lentes de Super16 que tan buenos recuerdos traen, o las lentes de 2/3”, pueden funcionar sobre nuestra FS7 II “solamente” sacrificando resolución. De hecho, esto ya lo hacíamos con el “modo APS-C” en la A7S, pasando de FF 4K a S35 Full HD.

¿QUÉ VARIANTES HAY?

Posiblemente lo haya comentado antes, pero es un artículo un poquito largo como para releerlo ahora. Las dos referencias que habrá para la FS7 II serán:

- PXW-FS7M2: sólo cuerpo de cámara

- PXW-FS7M2K: cuerpo de cámara con lente SELP18110G

En ambos casos se incluye cargador de baterías, alimentador AC/DC, batería BP-U30 (la pequeña), la visera plegable, el monocular, el dispositivo WiFi IFU-WLM3… vamos, que lo único que tendréis que tener a mano es la tarjeta XQD; mi consejo es que vayáis directamente a la serie G o S para tener todas las funciones (todos los códecs).

Disculpad si el artículo esta vez ha sido un poco más largo de lo habitual, pero teniendo en cuenta las similitudes con la FS7, prefería entrar en algo más de detalle.

De verdad, espero que os haya servido esta entrada, así como el vídeo de mi canal de YouTube; nos vemos… donde sea J